[Guest Essay by John Cooke — Teacher, Scholar, Actor, Retiree ]

“How the Pipeliner Likes His Eggs,” or Making a Buck on the Time Traveler Circuit

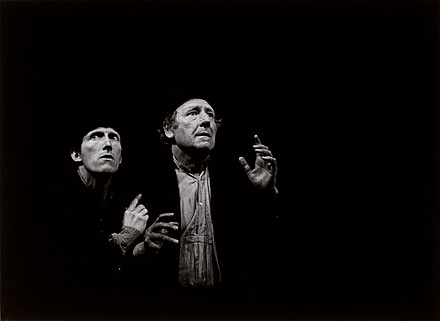

For a time when I was young, I was a “Time-Traveler.” Unlike the 2016 TV series in which two stoners discover a bong that can propel them through space and time, mine was just an acting gig. My time-traveling was somehow simultaneously more exotic and pedestrian.

My time travel involved telling stories about the feats of notable companies at live events across the country. I did this in character, the character in some way related to the company’s illustrious history.

But let me back up and tell you how my life as a time traveler came about.

After 11 years as a full-time theater professor, I left that business to return to acting and directing. I was 40 or so and knew that if I wished to live like an adult, this was a risk. Academia hardly left me overburdened with wealth, but compared to what I might expect from a life in professional theater, I had lived like a sultan.

But I was tired of talking about theater rather than doing it. Too many of my colleagues were poseurs: comfortable regaling teenagers with war stories about their “life in the theater” rather than teaching them anything. Either I feared becoming one of them or I needed to replenish my stock of war stories, I don’t know which, but with Chicago as my new home base, I re-entered a world I’d been away from for over a decade.

Virtually no actor makes a living exclusively from stage work. As in much of life, “follow the money” applies to acting as well. Except for the most successful practitioners, most of us have one or two affiliated sources of income, most frequently voiceover or print work or commercials. Totally by happenstance, following the money led me to an adjacent area called “industrial work.” Particularly in the last half of the preceding century, wealthy corporations bankrolled a vast array of instructional

or promotional productions, either live or via film and, later, video. If the company had deep-enough pockets, performers between gigs on Broadway gladly joined a live industrial; the production values of the film versions were of an equally respectable caliber.

Ultimately, I fell into a subset of that subset. I became, as noted earlier, a “Time Traveler.” The work paid well, and I demanded yet a greater fee because I was the equivalent of the famously versatile Veg-a-Matic: I could not only perform the script but do the research to create it. My character, costumed according to historical period, would then tell this story, rich in the company’s core values and rich heritage, to select audience(s) nationwide. With luck, these appearances could take up 20 or more work days of a year.

Time traveling paid my bills. If I had lifted my pinky, refusing all work outside “legitimate” theater, I could reasonably expect a lifestyle equivalent to a modestly comfortable grad student. By contrast, a day’s labor in the industrial market provided roughly what I could pull from two weeks on the stage—at a top-tier Chicago theater in a respectable role, mind you. Frankly, by middle age, I and most of my colleagues had long abandoned the romance of the starving artist. So, by adopting that admittedly jaundiced point of view, time traveling became the beneficent supporter of my stage work: it ensured the mortgage got paid while I pursued stage jobs, to my mind an acceptable quid pro quo. As Robert Graves, at heart a poet, once said of his financially successful novels, “prose books are the show dogs I breed and sell to support my cat, poetry.”

Time traveling normally comes in one of two forms: inside and outside. Outdoor events were often large company picnics, so you are competing against kids’ rides and contests and tables laden with free barbecue and pie. If inside, you are likely performing in front of hundreds of people in a more buttoned-up atmosphere. These were often not celebrations, but rather occasions for the higher levels of management to step away from office distractions and concentrate on the future of the business. There would be “focus groups” and “breakouts” and CEO speeches, team-building exercises and all-purpose shameless schmoozing. The time traveler was there as window dressing, a half hour break to allow attendees to clear their heads and check their messages. Engaged in either scenario, therefore, the time traveling actor could be assured that no one – abso-fucking-lutely no one – awoke that morning excited that I would soon grace their local stage.

While the money from time traveling made my life much easier, I hated that shit. So did most other serious actors who occasionally plowed the same field. To start with, it was hard work. Beyond their generous remuneration, one-person industrial gigs were known throughout the theater community for their daring and difficulty. When you shoot a commercial, for instance, you have a handler, a dedicated dressing room or trailer, the opportunity for second takes if things go awry and food readily available from craft services. Time travelers fly solo: get into costume in a remote bathroom, hoping no one intrudes while they apply makeup or perhaps a false mustache. Food? Hah. “Bobby’s got a grill set up over by the pony ride. He’s probably got an extra hot dog,” was the best you could hope for.

I assumed those indignities as part of the job. Throughout a day during which you might perform your bit a half dozen times, your mission was to present an earnest face to a public that most often did not understand who you were or why you were there. That’s because the people from headquarters -- that is, the people who formally hired me -- invariably made a mess of it from the get-go. I did probably 100 of these storytelling gigs for dozens of companies, and the handoff was always botched. The time traveler was just a freebee from Corporate, jammed down the throats of the on-site organizers and hence re-jammed down the throats of innocent attendees. A few weeks before the event, some senior manager from HQ would phone the local point person. “We’re going to send down this Time Traveler! He’s going to play one of our founders and tell stories from the early days. Folks will love it! Find him a place to give his talk.” Click. That would be the last guidance the earnest local contact would receive.

Given that setup, the detachment of my audience was understandable. Often, at company picnics, I’d take the stage and start talking, and if there were any audience at all it was most likely because Bill and Bonnie and the kids, after the rigors of ring toss, spotted some empty chairs and wanted to rest their feet. Despite this almost inevitable obstacle, those of us who did this kind of work adhered to one firm rule: Do exactly what you were hired to do. Just because there’s no audience, or an audience that continued to talk amongst themselves while daubing ketchup off their tank tops, you delivered your best.

I was working a company picnic close to Natchez, Mississippi, once, when one of the audience members picked up her baby, walked to the lip of the stage immediately below my feet and proceeded to change the lad’s loaded diaper. With considerable effort, I brushed aside reflections on the existential chasm now standing between me and those frolicsome days in the faculty lounge. Instead, I ignored the deposit little Davey had gifted me, after what must have been a particularly robust breakfast, pushing on with artful purpose, as if one of those lovely begowned ladies at the Oscars had just presented me with a dozen roses. Time travelers have an Olympian work ethic.

I’ll take you now to the event from which derives my title. It’s the mid-1990s and so far I’ve enjoyed a good year. A long run in a downtown theater was already under my belt, as well as a couple of commercials and some new-play development. I was now setting out to fulfill a number of bookings in the time traveler department. Summer was particularly good because of company picnics, so I was often engaged most weekends throughout that season. If my plans came to fruition, a modest off-season vacation might be in the offing.

One of the few benefits of this kind of work is the opportunity to see a lot of America. All expenses were paid, so I’d book a good hotel (if there were any) and eat high off the corporate hog. This particular one-man show was at a rustic but well-appointed fishing lodge in the Ozark Mountains. My client was a large natural gas company with a respected history. The attendees at this event were clients: local officials from throughout the Midwest and Great Plains who bought the company’s gas to serve their local citizenry. Most likely, I was told, they held this public job while also farming a few acres on the side. A couple of days of fishing and food – and an appearance by yours truly – was their reward for remaining dependable customers. Early that morning, I flew from Chicago to Little Rock, rented a car and motored a few hours north into Missouri and the picturesque Ozarks.

Because my on-site contact people rarely have any fucking idea why I’m there or what for God’s sake could be my purpose, they often get nervous and start giving me things. I’ve acquired t-shirts and gimme caps and even nicer swag from all over America, courtesy of hapless handlers befuddled and yet determined to treat this stranger with respect. My handler here in the Ozarks, a nice but twitchy lady in her fifties, wants me to join the attendees for some fishing on the river sluicing just below the lodge. Though I love to fish, I declined. Interacting with my future audience as “John the actor” is never a good idea, and besides, flying and driving had worn me out, and in two hours, I’ll be “on.”

I try to nap but fail. It’s show time. I run my lines and check my costume, which I imagine conveys a good ol’ boy look not unlike that of my upcoming audience, only slightly more dated. I find my starting point, the top of a staircase leading down into an ample dining room with décor reflecting the lodge’s rural setting. These guys have been fishing all day, and they’re now tucking in to eat their catch. This is my cue. Like a countrified Stentor, I commence, booming out a 15-minute story about the founding of the company and its heroics during World War II.

Actually, their achievement was heroic. To supply natural gas to wartime factories, they built a 1,300-mile pipeline from close to the Mexican border in Texas into Ohio, through mountains and over rivers and swamps, in less than 18 months. So in a way, I’m rather proud to be playing one of the company’s actual old-time pipeliners from that period. Nevertheless, after a perfunctory glance at the loudmouth descending the staircase, my audience, numbering about a hundred, mostly continues to explore the riches plated before them. Have they presumed I’m one of them, my animated enthusiasm attributable to over-exuberance at the evening’s open bar? Some occasionally suspend their forkwork long enough to listen to a sentence or two, but in this competition, I’m placing well behind the butter beans and corn. Nonetheless, I like telling stories, so this part is actually fun, despite the inattention.

As I’m wrapping up, my audience is at that dinnertime Rubicon when one must either bust a move for seconds or commit to the banana pudding. I take this moment to bless these great Americans for their kind attention and retreat from sight.

Normally, after a “show,” I wish no further contact with the client or audience, not because I dislike them, but because it keeps the experience tidier if I call no attention to myself as “the actor from Chicago.” But dining options aren’t abundant in the stately Ozarks. Beyond this dining room, where I have just delivered the definitive pipeline Lear, there is no place to eat for miles. So, still in costume but carefully avoiding eye contact, I discreetly fill my plate fried trout and fixin’s and ease into a vacant corner banquet.

The food is terrific and I shovel it down quickly. On these jobs, once provided my evening meal, my plans usually roll out with regimental precision: return to my room, crack the pint of bourbon that’s been my longstanding companion on such expeditions, enjoy a swig and call my lovely wife. After that, I might enjoy another tug or two while consulting CNN, followed by bedtime and tomorrow’s early-as-possible dash for home. But on this occasion, I was forced to abandon that predictable regimen.

Comfortably sequestered and now sated, I am admiring the abundance of mounted fish and wildlife festooning the knotty pine walls about me when something strange happens. While I happen to be digging deep into my craw in an attempt to dislodge a fishbone, two of my audience members approach the table. “That was some story,” says this nice guy from one of the flyover states. “I can’t believe you guys did that.”

Once I’ve met my most immediate challenge, dislodging the fishbone, I try to process what I’ve just heard. I was experiencing what I think people refer to as “cognitive dissonance.” “I know nobody in this room went to MIT,” says I to myself, “but surely they have a sufficient facility with addition and subtraction to realize that I, quite clearly in my mid-40s, could not possibly have been a pipeliner – or any fucking thing else – during World War II.”

While this conclusion is taking its final shape, my fan’s follow-up query opens up paths to this point unimagined: “We’re going to play a little poker. You want to sit in?”

Thus ambushed, I said yes. To this day, I’m not sure why. What’s being suggested is that I spend hours at a poker table within inches of six or so strangers, pretending to be someone who by any rational account died thirty years ago. Galapagos tortoises are normally more capricious than I, but perhaps the notion arose within me that this might be an intriguing option to my well-established and frankly dull post-show routine.

I return to my room for my bottle, still unsure whom they think they just invited to the table, but my best judgment tells me to show up as The Ol’ Pipeliner. Actually, I’m not too worried. If things become ridiculous, I can simply thank them for the card game and retreat.

Upon entering the card room, my new friend introduces me by the name of the pipeliner I had just embodied. I am he. Over the previous two months, I had written and performed on-camera narration for a documentary about this company, so I could only trust that I was armed with enough bullshit to maintain my ruse. As the first few hands are dealt, I field a few questions with vague but plausible answers or outright deflections. “You guys are takin’ all my money. Let me concentrate on the crap I just got dealt and I’ll get back to pipelining later.” But it soon becomes obvious that my lousy poker is actually to my favor, as their interest shifts from me to my money. Either their natural good manners prohibited further probing or they ultimately found me uninteresting. So we soon settle down to a relatively pedestrian round of seven card stud.

I fake it at the table for about 90 minutes before folding my last lousy hand. Back in the room, I call my wife to tell her about my adventure and the 20 bucks I lost. I then look over a scene for an upcoming audition, a callback for a verbally nimble Tom Stoppard piece that requires study. Breakfast starts at 6:30, but I’ll take a pass: best to depart unseen so that no one becomes interested in how the pipeliner likes his eggs.